Drench Resistance

Drench resistance is a change in the genes of a worm population that enables some worms to survive drenching. Drench resistance is a farm problem. Resistant genes can be purchased with stock or with land. Destocking will not get rid of resistant worms, as most of the worm population is on the pasture.

How does drench resistance develop?

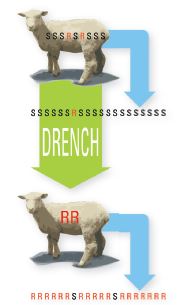

Before drenching, most worms on a farm carry genes that make them susceptible (S) to a drench family; that is, they will be killed by the drench. On the other hand, a smaller proportion of worms will carry genes for resistance (R).

The speed at which drench resistance develops on a farm is extremely variable – from a few years to several decades – and is dependent on the selection pressure for resistant worms (refer to risk factors below). If stock are drenched, some worms carrying resistant genes will survive drenching. These survivors can then mate and produce resistant eggs that are shed in the faeces onto the paddock.

If environmental conditions are favourable for egg hatching and larval development, then the proportion of R to S larvae may gradually increase over time on the pasture. It is this proportion of resistant to susceptible worms on pasture that is important. Long-acting drenches increase the speed at which resistance develops.

Short-acting drenches are active for just a few days after use; therefore, if stock graze contaminated pasture a few days after drenching, the susceptible worm larvae will develop inside the animal, mate and produce eggs about 21 days after being eaten (prepatent period). These susceptible eggs in the faeces dilute out the resistant eggs (from worms that have survived drenching) also being deposited on to pasture.

Risk factors associated with acceleration of drench resistance.

- Drenching adult ewes pre-lambing – especially with long-acting products such as drench capsules and long-acting moxidectin injections is likely to be more selective for drench resistance.

- Purchasing sheep or cattle without a quarantine drench i.e., administering an effective drench, or combination of drenches (preferably Zolvix® Plus (A11107), or Startect® (A10353), in combination with Scanda) and holding livestock for 24 hours in yards or a holding area with food and water before allowing them access to the main grazing areas, will go a long way to reduce the risk of introducing drench-resistant worms onto your farm.

- Drenching lambs or calves onto ‘clean’ pasture e.g., new pasture, hay or silage aftermath, and pastures where alternative livestock species have been exclusively grazing for >3 months. Leaving a proportion of young stock undrenched (2-10%), or allowing lambs or calves to graze on known contaminated areas for 3-5 days after drenching, before going onto clean pastures will help to reduce the risk.

- Drenching of young stock – routinely drenching lambs or calves within 28-day intervals is likely to increase the risk of drench resistance. Although it is common practice to drench at 28-day intervals, this will select for some degree for drench resistance. The risk can be reduced by:

(1) rotationally grazing undrenched ewes after lambs,

(2) leaving a small proportion of lambs or calves undrenched; and

(3) spreading out the drenching interval (at least 28 days) allowing worms not exposed to drench to complete their life cycle (and lay eggs). Care needs to be taken when extending drenching intervals to ensure that animal performance and/or welfare is not compromised. - Use combination drenches – the best time to use Alliance is before drench resistance has established.

- Under-dosing – to ensure that your drench gun is delivering the correct dose, squirt 10 doses of drench into a measuring column, and divide the total volume by 10, to ensure that your drench gun is delivering the correct dose. We recommend this be done before every new day of drenching.

- Drench rotation – rotating drench families annually is a past practice but there is no evidence that this strategy will slow the onset of resistance. Monitoring drench efficacy using faecal egg counting 10 days after drenching (FEC10) at least twice a season, and using a triple combination drench like Alliance before drench resistance develops, is advised.

How do you diagnose drench resistance?

Diagnosing resistance by judging the performance of a drench based on “dags, weight loss or death” is not an accurate measure of resistance on your property. By the time drench resistance becomes apparent based on these indicators, major production loss and pasture contamination is likely; and may have been occurring for years. On the other hand, poor response to drenching may not be due to resistance.

For example, something as simple as drench gun failure can be behind the apparent failure of a drench. The only way to know if a particular drench is working on your farm is to do regular (every 3–5 years) faecal egg count reduction tests (FECRTs). A FECRT gives a detailed breakdown of drench efficacy, including the resistance status of individual worm species. Advice should be sought to ensure that it is performed correctly, at the right time, and is interpreted appropriately.

It is also important to continue to monitor drench efficacy after conducting a FECRT. Doing two simple drench checks a year – ideally one in spring and another in autumn, will provide you with confidence that the drench that you are using is continuing to be effective. A drench check is when a faecal egg count is conducted 10-14 days after drenching (FEC10).